Mountain Metrics

Mountain Metrics

Why Not All Miles in the Mountains Are Created Equal

With a rapidly growing outdoor industry and more people getting outside than ever, there’s an increasing need to understand what it actually means to move through the mountains.

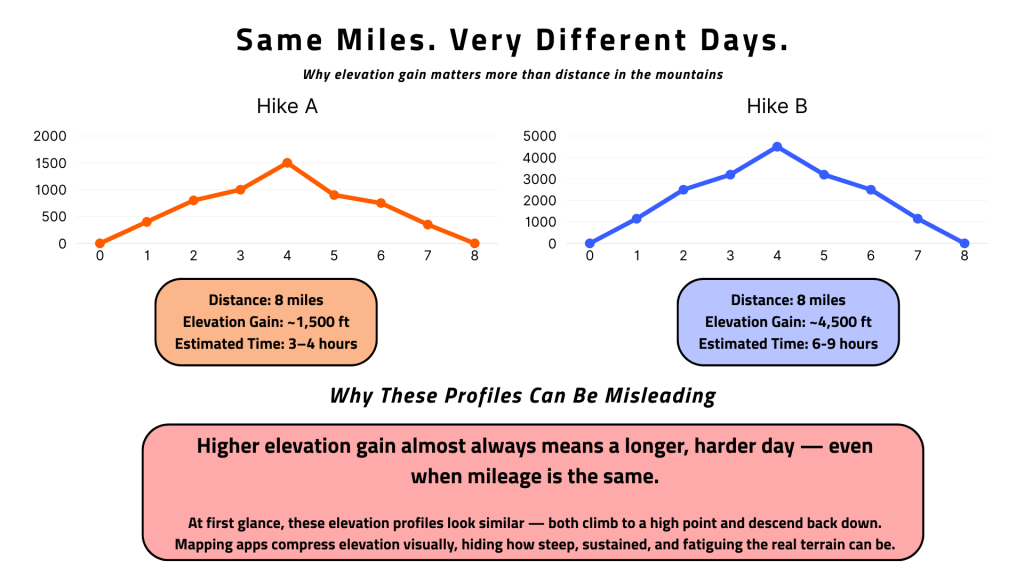

One of the most common planning mistakes we see, especially among newer hikers, is assuming that mileage alone tells the story. “It’s only X miles,” or “AllTrails says it’ll take 4 hours,” often leads people into longer, harder, and riskier days than they expected.

This resource is designed to help hikers, backpackers, and aspiring mountaineers better understand the metrics that actually matter when traveling in mountainous terrain. This will can help you plan more effectively, move more efficiently, and have safer, more enjoyable experiences.

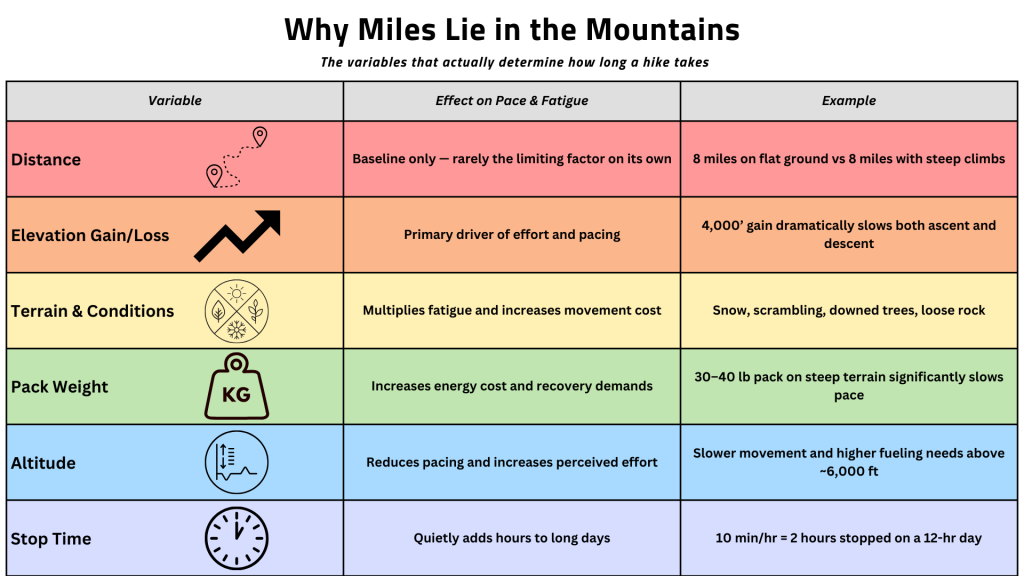

We’ll explore how terrain, trail conditions, elevation gain and loss, altitude, pack weight, fitness, and stop time all impact effort and pacing, often far more than distance alone. By the end, you’ll have a clearer way to estimate how long a hike will actually take and how to prepare for it.

Time is The Real Metric

When moving through the mountains, time, not distance, is the most honest metric.

This is why many European trails list time instead of mileage or elevation gain. While that approach has its own limitations, it reflects an important truth: how long something takes depends on far more than how far it is.

Your pace will change dramatically based on:

- Elevation gain and descent

- Terrain and technical difficulty

- Trail conditions

- Altitude

- Pack weight

- Fitness and experience

- Stop time

When these variables stack, underestimating time becomes one of the most common pathways to fatigue, poor decision-making, and increased risk.

Making Miles

On flat ground, most people fall into a relatively predictable walking pace. While individual fitness varies, there’s only so fast most people can walk comfortably over time—even when fitness is high.

This information matters not because flat ground defines mountain travel, but because it establishes a baseline. Knowing how many miles per hour you can cover on flat terrain gives you a reference point for understanding how dramatically other variables will slow you down.

Pack weight doesn’t make a huge difference here, and while running or jogging obviously increases pace, that’s not the focus of this discussion. Flat mileage is simply the starting point for understanding movement efficiency.

Most trails around the world indicate time rather than distance. This, of course, is still a subjective guess at best.

Flat urban miles feel like a breeze after big days in the mountains

Elevation Gain & Loss

The Biggest Drive of Time on Trail

Elevation gain and descent are often the single biggest variables impacting time on trail.

Most people underestimate how much both uphill and downhill will slow their pace. A more useful metric here than miles per hour is vertical feet (or meters) per hour, especially on sustained climbs.

Controlled assessments like treadmill or StairMaster tests can provide insight into uphill capacity. However, these are highly controlled environments and don’t always translate cleanly to real mountains.

On actual terrain, uneven footing, variable slope angles, and fatigue all come into play. Slope angle matters tremendously:

- Long, moderate climbs may allow for higher miles per hour

- Steep climbs over short distances may yield high vertical feet per hour but slow overall movement

Understanding this tradeoff is critical when estimating total time.

Vertical feet per hour is the ultimate metric when tackling serious elevation gain.

Big descents can take just as long, if not longer, than the way up

Munter Rate

A Rough Planning Tool

Many climbers and professional guides use time-based pacing systems like the Munter Method, which estimate travel time using a combination of horizontal distance and elevation gain.

Used well, Munter can provide a rough starting point for planning. However, it assumes relatively consistent terrain and movement and does not account for many real-world variables like trail conditions, technical terrain, altitude, fitness, or stop time.

In the mountains, Munter is best thought of as a baseline estimate, not a guarantee. Real-world travel requires layering in conditions, terrain, and how efficiently you manage your time on the move.

Elevation gain on supportable snow is sometimes faster than on the trail

Terrain & Trail Conditions

When Estimations Break Down

Trail conditions can slow you down just as much—or more—than elevation gain.

Snow, downed logs, creek crossings, loose rock, bushwhacking, scrambling, off-trail travel, and burn zones all add time, fatigue, and complexity. Technicality and experience level matter enormously.

Consider a few real-world examples:

- Half Dome: long mileage, significant elevation gain, and a technical finish where waiting for others on the cables can dramatically impact total time.

- Mount Shasta: fewer miles, far more elevation gain, higher altitude, and technical snow and ice climbing—often turning a 13-mile route into a 20+ hour effort for many climbers.

- Winter travel on skis: breaking trail in deep snow with a heavy pack can be brutally slow, while firm snow conditions can allow for surprisingly efficient movement.

Terrain and conditions don’t just add effort—they multiply it.

Half Domes cable section will inevitable slow your pace

Moving through fresh snow or rocky terrain will not only slow your pace, but likely require more route finding as well

Stop Time

The Silent Multiplier

Stop time is one of the most overlooked contributors to long days in the mountains.

Every minute you’re not moving adds to total exposure, fatigue, and risk. Even small breaks compound quickly. A 10-minute break every hour on a 12-hour day adds up to two full hours of stop time.

In guiding contexts—such as with Shasta Mountain Guides—a common practice is moving for approximately 60 minutes followed by a short, intentional break to fuel and hydrate. This approach helps manage fatigue while minimizing unnecessary exposure.

Unmanaged stop time can:

- Kill momentum

- Increase stiffness

- Open the door to compounding problems later in the day

This isn’t about not enjoying the experience—it’s about understanding when efficiency matters. There’s a time and place for lingering, and a time when moving efficiently is the safer, more sustainable choice.

The Effects of Altitude

The Great Equalizer

Altitude and reduced oxygen availability will slow your pace—often more than people expect.

While this piece doesn’t dive deeply into acclimatization, it’s important to recognize that even above ~6,000 feet, many people experience diminished pacing and altered fueling needs.

In guiding scenarios, the goal is often to move efficiently up and back down before altitude effects compound. Acclimatization takes time, and three days is often not enough.

A deeper dive on altitude and acclimatization will be covered separately.

Trekking in Nepal at 15,000′ in Sagarmatha National Park

showing up prepared

The only variable you can control

Many of the variables discussed like terrain, snowpack, weather, and trail conditions are out of your control.

This is where fitness stops being about performance and starts becoming a safety margin.

Effective training allows you to:

- Maintain efficiency in poor conditions

- Recover faster from technical terrain

- Manage long days with less fatigue

- Better estimate time, food, and water needs

This is why training hikes are so important. They allow you to test systems, experiment with fueling strategies, and understand how your body responds to real terrain, not just gym equipment.

The StairMaster alone won’t cut it. Mountain movement demands strength, stability, endurance, and adaptability.

Full body and multiplanar movements are some of the best ways to train for dynamic terrain

Unilateral lower body exercises build stability, endurance and grit for big days in the mountains

Planning Ahead

Safety & Sustainability

Planning ahead and preparing appropriately isn’t just about performance, it’s about being a responsible member of the outdoor community.

When you understand what it actually means to move through the mountains, you can plan better, reduce risk, and create safer, more enjoyable experiences for yourself and those around you.

Stay safe and enjoy your adventures!